I’m sitting at the base of a gnarled pinion pine tree in the middle of the woods behind the Bader-Snyder complex. It’s dark and the rain has been pounding the saturated soil relentlessly, but I am dry, and looking up at my protector, the arching branches that stretch around me like arms.

The smell of earth, wet bark and seeping sap mingle in my nose as I close my eyes, work my toes deeper into the dirt and press my hand to my aching heart.

This isn’t just any old tree. It’s the Zoe tree.

It’s adorned in shimmering beads that dangle and dance in the air. A wood sign is painted with the name Zoe and surrounded by flowers, rivers, mountains, and fire, and is nailed to a prominent bough. There’s a small pink ski that sits in the trunk. Individual mementos stand by the roots, like little soldiers protecting their base. Sitting on one side is a chair made of rocks that were carefully placed and painted. Bunches of flowers occupy the space as well because what is a memorial without wilting petals?

This is the dedicated memorial to my roommate and dear friend, Zoe Coughlin-Glaser, who died in a car accident right before this school year started.

The tree is a place to bring people together and closer to the memory of her, in the woods that she explored and ran rampant in, surrounded by frisbee golfers and wandering students, this is where she can be remembered.

Looking up into the arms of the Zoe Tree

Zoe was a biology student at Fort Lewis College who lived life more curiously than anyone I’ve ever met. She raced for the Alpine Ski Team on campus, joined the pottery club, created art, consumed new music every day, changed her hair at the drop of a dime, collected rocks and disregarded objects that no one else would notice, cared for plants and cats and made friends wherever she went.

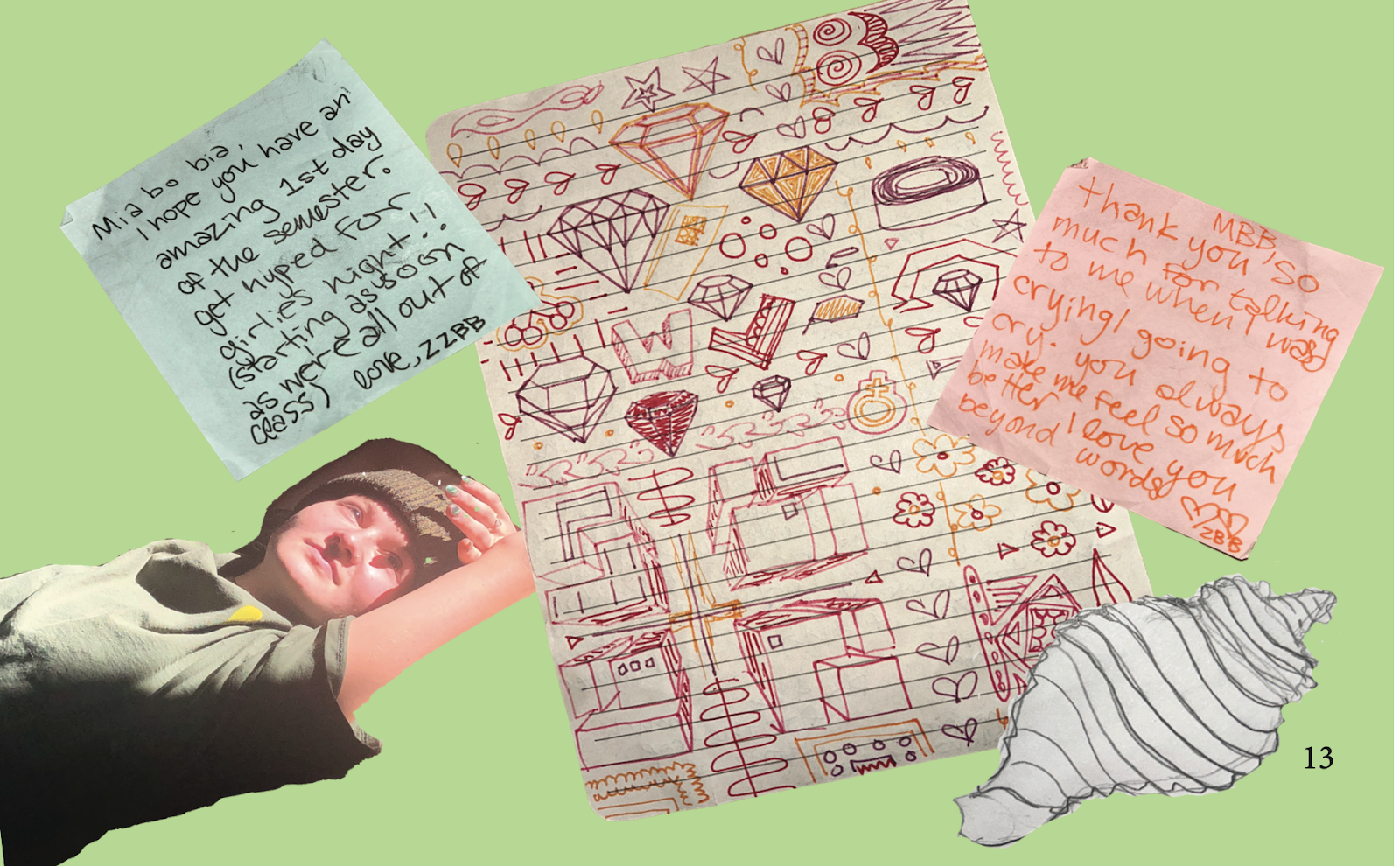

There was never a day that she let pass her idly by. I would come home, and she’d be crouched on the floor or at the dining room table, surrounded by beads or colored pens with her journal open, ready to tell me her thoughts and stories, and I miss her.

Since Zoe died, I’ve been feeling your presence very close to me, Death, and I have questions.

Why am I writing this? Is it to find some sort of closure? To commemorate the life of my friend who touched so many others in Durango? Or am I just a maniac who likes to dwell in the pain of it all? Yes, yes and maybe.

What feels the most correct to me, is my existential need to face death head on and not be afraid to grapple with it.

But what does it all mean? To live, to love, to connect, to be a human, to die, and to move forward, for both the people leaving and the ones who get to stay.

All humans think about death. It’s one universal factor besides birth that we have to deal with at some point. It’s inevitable and can be scary.

So, what is death, and why are we so afraid of it?

Christine Pollock is an end-of-life doula who for 15 years has been working with dying people and their families to help them work through their baggage and fears regarding death, and try to create a sacred, loving and clear space for those who are transitioning.

Pollock said that the experience is very beautiful, and that her line of work is an honor and something that chose her after she supported a close friend at the end of her life.

Death is on the other end of birth, is a part of life, and the two are not in opposition to each other, she said. Death is the great unknown, and is only what we can imagine it to be.

“We enter into this world in a form, and we’re going to exit this world and leave the form,” Pollock said.

Dr. Brian Burke, a psychology professor at FLC, said that humans, as far as we know, are the only species aware of our inevitable death, and therefore we can project ourselves into the distant future and imagine what the process might be like.

He said that although this can be a great advantage, to be able to plan and build a future, it’s also terrifying and a problem of survival that humans have to deal with.

The Terror Management Theory, created by the social psychologists, Jeff Greenberg, Tom Pyszczynski and Sheldon Solomon, helps people cope with their conscious or subconscious fears of death and threats to existence by investing deeper into one’s cultural worldviews, the things that we feel most connected to, in order to protect us from those fears, Burke said.

This theory was inspired by the work of Ernest Becker, a cultural anthropologist, who believed that as humans, we want to live a meaningful life and be considered as a valuable contributor to our own chosen groups, he said.

“I think that's why, when we're thinking of death, we come back to that cultural worldview,” Burke said. “Because we need the feeling of self-esteem, which is a fancy word for just saying we need to feel like we're a valued part of something.”

After Zoe’s death, I found myself searching for my place in the world without her.

I remember the morning vividly when I found out that she had passed. I was sitting on the edge of my bed in my pajamas, when her dad called and told me what happened.

I started crying, shrieking, repeating the words, ‘oh my god’, over and over again, throwing on a long white dress before running barefoot down the street, two blocks to our friends house, the one Zoe was planning to move into, where I clutched the porch railing with white knuckles and uttered the news for the first time.

More people came to the house as the news spread. We all reeled in the shock of death and shared stories about Zoe, trying to feel her spirit through human connection.

It’s a natural human reaction, as interpersonal creatures, Burke said, to run towards other people and loved ones when we are faced with danger. In this case, the death of a dear friend.

In the face of death, I have been, and still am, running towards the people that will hug me and cry with me, as we attempt to keep each other safe.

Finding connections that make sense to the individual person—whether that be to people, nature, animals or anything else one values is crucial when dealing with death, Burke said.

Burke teaches a class on positive psychology, he said, and one of the things he teaches is that finding happiness comes from forming relationships.

Zoe and her notes and doodles

As I’ve grappled with Zoe’s passing, I’ve found myself trying to find deeper meaning through my friendships, through my work as editor-in-chief, my role as a student and my passion for dance. But I can’t help but wonder: what makes a life meaningful and valuable?

“There are many different threads, because this is basically the question of what makes a life worth living,” Dr. Justin McBrayer, a philosophy professor at FLC, said. “And sometimes when I teach intro to philosophy, that's the last unit of our class, and we go through four or five different theories. But the short of it is, philosophers don't agree.”

Socrates believed that the unexamined life isn’t worth the price you’re paying for it, and in a human’s case, that price is the one shot we have at earthly life, our only ticket, McBrayer said.

If we spend that ticket on a life we haven’t thought carefully about, it isn’t worth it, so we want to make sure to put our best effort into our only shot at this life, McBrayer said.

“One theory says that your life goes well, when you get what you want,”he said. “That's it. Lives are just about, you know, getting what you want. They're about maximizing preference, satisfaction, you have desires, and when they go unmet your life goes badly. When they get met your life goes well, that's all that matters. Other people say, no, that's crazy. You could be a serial killer, and what you want is to kill people. And now what you're telling me is that your life's a good one when you kill as many people as you can. That's actually what the theory seems to say.”

Other philosophers, McBrayer said, believe that a life is well lived if the person has things that are objectively good, like friends, healthy food or endless knowledge. The problem with that, he said, is that if a person has things in their life that are objectively good, but aren’t making them happy, then is that still a life well lived?

The final theory, McBrayer said, is a mix of both, a life well lived is one where a person has objectively good things in their life, and they are things the person wanted and recognized to be good.

Irvin Yalom, Burke said, is an existential psychiatrist who conducted studies with terminal cancer patients. He found that the reason death is so scary to some people is inversely proportional to how well someone has felt they’ve lived their life.

“If you have a lot of unlived life, and you have a lot of regret, your fear of death will be stronger,” Burke said. “The research shows you're going to fear death more, if you feel like you haven't lived well, or you've waited too long to live your life.”

Burke said that people also fear how their loved ones will get by without them, and that they might miss out on important events.

That’s why, as Yalom puts it, the way to deal with death is to have less unlived life inside of you, shore up your relationships and try to become more and more comfortable with the uncertainty of the great unknown, Burke said.

“I will say personally, none of those work for me,” Burke said. “I'm 51 years old and terrified of death. And I think about my death very, very often, maybe not every day, but certainly on a weekly basis.”

Pollock said that death can be tainted by the baggage, unresolved issues, conflicts or veils of perception of what death and the afterlife might be like.

She helps people who are about to die work through the fear, regrets and baggage they may have by reviewing the person’s life with them as a way to be more present, Pollock said.

These reviews can look very different depending on the person.

“You can even break it down into decades,” Pollock said. “What was the most important thing that happened? Who were the people in your life? How did they transform your life? You know, what were the lessons you learned?”

She said that people have to believe that we are a finite self in our physical bodies, and acknowledging and accepting this impermanence of who we are can help us start living in the present fully.

“It's about impermanence,” Pollock said. “It's about meeting every moment in the now without bringing all that baggage. Death is happening in every moment of our life, and when we can bring our true loving self to every moment, we are allowing for death to happen.”

I wish I could ask Zoe about her life, how she felt about death and whether or not she felt she had lived well.

In my view of her, I think she did, but she had so much left to do. She was only 20, after all. For the time that she was here though, she seized the opportunities that were presented to her with love and relentless courage.

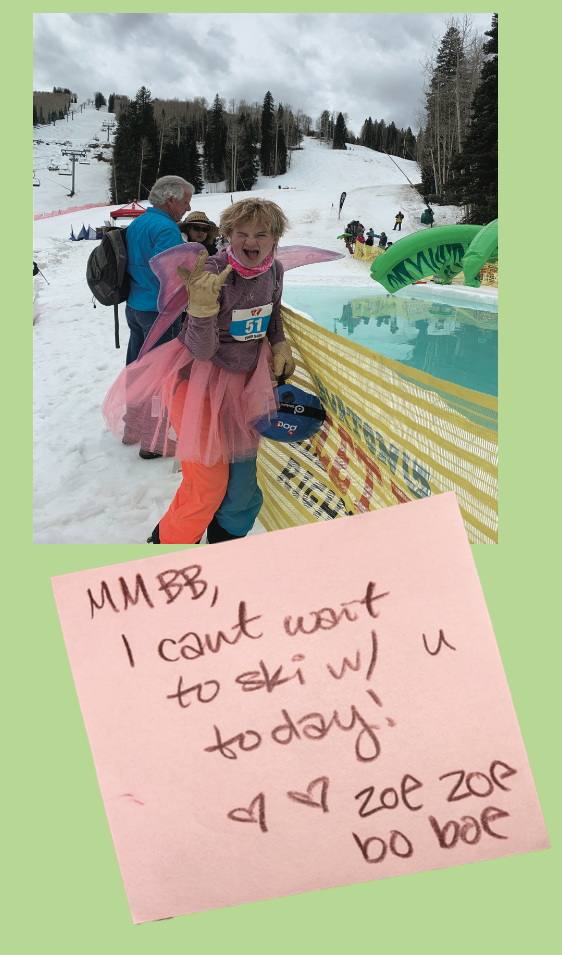

At the end of the ski season, Purgatory Ski Resort holds an annual pond skim, where riders can fly down the hill at full-speed until they reach the edge of a shallow pond to ideally glide across with steez or style.

In the spring of 2022, Zoe and I signed up bright and early, took a few laps and made our way down to the crowd of riders in tutus, Hawaiian shirts and crazy end-of-season garments, all standing around the man-made pond waiting to be entertained.

Zoe was dressed in her notorious ski pants, with one leg bright blue and the other bright pink. She was always the easiest person to spot on the mountain. Over the pants she wore her “ski bum” underwear, a hand-made tutu, and glittery butterfly wings that matched her personality—big and colorful.

Zoe in her ski garb!

I was scared and kept second-guessing whether I wanted to ski down in front of an audience. While I wallowed in anxiety at the bottom of the hill, Zoe was already half-way up it, hiking to the starting point.

Before I knew it, I watched as my best friend, #51, came cruising down, hit the water, cut the surface, slid across effortlessly and stuck her steezy landing on the other side. Once she did it, I knew I had to as well. She made everything feel possible, and approached every situation with innocence and excitement.

Sure enough, I found myself hiking up to the top of that hill too, waiting in line, breathing, and then sending it full-speed down the mountain. ‘You got this, lean back, balance, get steezy.’ I hit the water, flew across the pond, and shot into the air. Woohoo! That rocked!

I skied up to her after my turn was over, and she hugged me, told me how awesome I looked and said,

“See, I knew you could do it!”

Zoe, #51, at the pond skim looking steezy.

If we live life well, like Zoe, is death still a bad thing?

Some philosophers, McBrayer said, believe that death is the worst thing that can happen because our existence is necessary for us to experience more life.

McBrayer called this a deprivation view, because death is depriving us of having more future moments that we deem to be good. The little things, like a first kiss, climbing a mountain or eating an incredible meal.

However, some philosophers also believe that death can be a good thing, McBrayer said.

Bernard Williams, a British philosopher, is best known for defending the idea that death provides meaning to the rest of life, and if humans were to live infinitely, life wouldn’t be as valuable. He thought that death may be feared or considered bad but really, it is what infuses life with purpose, and is an important factor that gives value to every moment, McBrayer said.

“I do think fear of death can be helpful as well, because I'm not as lazy as many people that I know,” Burke said. “For example, I'm often out on the trails doing something. I don't sit at home that often, and I think some of that is because of my fear of death. It spurs me into wanting to do something, wanting to get out there and see the sunset and, you know, go on a bike ride or hike or whatever the case may be.”

Pollock described death as neither good nor bad, but as a new experience that we will all have for the first time with a naked eye and child-like innocence.

“My hopes and dreams for people are that through their own awareness and practices, that they can come to experience death as very much an integral part of life, and that they're entering into it in this place of sacredness, in this place of curiosity, in this place of innocence and that it's very much ongoing in every moment,” Pollock said.

Zoe always loved a new experience.

This past spring, Zoe, our group of girlfriends and I headed to Moab to reaffirm our wild womanhood in the desert.

After a fun day of climbing topless on walls of red sandstone, we made our way down rocky dirt roads to the Fruit Bowl highlining area to meet up with some Durango highliners and see what it was all about.

Highlines are slacklines suspended in high places, and anchored to two opposing sides of large cliffs, it’s quite the view.

When we arrived, there were about ten people, standing on one side of a large deep canyon, some with juggling pins, one with a twirling baton and most watching the three highlines, more importantly the people on them, suspended 500 feet in the air.

I was in awe when one of our pals asked if any of us wanted to try zip-lining to the middle of the line to check out the scenery.

We all looked at each other nervously, and then Zoe broke the silence by saying,

“I will! Can you show me how to do it?”

Before long, Zoe was stepping into a harness, being attached to the highline and zipping out into open air. She laughed, looked around, bounced and started trying to do some tricks.

After that, the rest of us went out too, because Zoe made it look too fun not to try.

Zoe and I in Moab.

She had such an incredibly large personality that when she passed away, it was hard to not have the physical version of her anymore. I could feel her larger-than-life essence, but needed a way to materialize her, to bring her back into a form that I could visibly understand.

“I think for many people, we can more easily understand things if it's concretized, if it's made into some sort of physical piece,” Burke said. “Which is why I think almost every religion or culture in the world has some version of that.”

Like the Taj Mahal or the Egyptian pyramids, Zoe’s community decorated a tree that felt big enough and strong enough to honor her properly. Although it might not be considered a feat of architectural genius, it gives us a space to grieve her in a tangible way.

Burke said that one goal of grief is to have a continuing relationship with the people we’ve lost. Whether this be through ritual, culture or having pieces of remembrance to keep them alive in spirit.

Grief is love, Pollock said.

“I believe the power in all of this is in sharing and acknowledging,” she said. “You know, whether that be through ceremony or just open, honest heart discussions with people, I think the more that we can accept.”

Death to her is a contemplation, a meditation, a relaxation and deep self-inquiry, Pollock said.

Psychological research shows that less avoidance is better, Burke said, and that exposing ourselves to death at funerals or other rituals can help us face the fear head on to try and understand it.

Burke said that sharing experiences about the loss to other people, in journals or in imaginary conversations with the one who has passed can be helpful instead of denying the reality.

It’s important to see the gifts that your loved ones left behind, Pollock said. She ended our interview by asking what the gift or diamond Zoe left in me was.

I believe Zoe left behind so many little diamonds.

In the thunderous rain that slams down on the pavement, echoes sound through the trees, erupts lightning in the mountains and leaves dirty puddles to play in. I catch whiffs of her in the downpour and am graced by her wild spirit when the droplets kiss my face.

I remember the little moments with her: Our adventures, climbing, skiing, exploring random roads and trails, our late night conversations, our dance parties and scream singing sessions, our little notes that we wrote to each other, our girlies nights and crawling into each other's beds in the morning. She was my first roommate and the closest thing I had to a sister.

The last time I saw Zoe was over the summer in her childhood home in Portland, Oregon. It was the first time I’d visited her place of origin and she spent a good hour showing me all her plants and little mementos in her room and telling me the story of where each thing came from.

That night, we slept in the bed she grew up in. In the morning, I woke up before her and thought about how comfortable we had become with each other.

We met as random strangers in the dorms two years ago and now, laying there, I couldn’t imagine my life without her. We always talked about what would’ve happened if we weren’t assigned as roommates freshman year. Would we have still met? Would we have still become such close friends? We always came to the conclusion that we would’ve found our way to each other somehow, and if we didn’t…Well, we didn’t want to think about that.

Zoe and I were different, we had different styles and ways of approaching life, but we worked well together. We were each other’s support system, our home away from home, and she was the best playmate I’ve ever had.

After we woke up that morning, we laughed, took pictures and then she hugged me goodbye on her front lawn wearing a spongebob shirt and boxers, and told me she loved me and would see me again soon.

Now, I’m living without her but I feel her always. I’m hurting, but when little life moments happen I think about what she’d say or how she’d react and it makes me smile.

I see her in the glorious sunsets, where bright colors blast across the sky, as if she took a brush, carefully mixed the warm-colored paints together, and streaked lines through the clouds to say, “I am still here.”

She was the bravest, loudest, silliest, most effortlessly artistic person I will ever get the pleasure to know, and I will carry pieces of her with me always.

I’m walking through the forest again, it’s daytime now and my classes have ended. A beautiful sun is starting to melt into the horizon, and I can see light coming through the branches of the Zoe tree, the rays bounce off the beads like a lighthouse guiding its ship safely home. I put my backpack down and lie in the dirt, looking up at the sign and the pink ski as I put my airpods in. I open my phone and my thumb moves to the call button, scrolling through my voicemails until I find the last one Zoe left me. I click play.

Her voice rings in my ear, and the tears start to stream down my face. After the 39 seconds are up, one of her sentences still echoes through my mind.

“I hope you have a good day, a good week, a good summer and a good life.”

Okay, Zoe. Just for you.

The Zoe Tree in all its glory