Cover photo courtesy of Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Wolf 2306-OR runs into the wild after being released by CPW on Dec.19, 2023.

Grand County is a land of wide open skies, snowy mountains that hunch against the biting wind blowing off the plains of Wyoming, and miles and miles of prairie, pine forests and meandering trout streams. It’s home to the headwaters of the Colorado River, massive herds of elk and pronghorn, and some 15,000 people who live in and around the string of little ski and cattle ranching towns dotting Highway 40 as it roves through rolling hills cloaked in sagebrush, piñon pine and stands of aspen.

But at the end of 2023, Grand County became home to a new group of residents: gray wolves.

Whether or not that’s a good thing depends on who you ask.

In a video released by Colorado Parks and Wildlife on Dec. 18, 2023, a group of 45 people—including Gov. Jared Polis, CPW officers, state officials, invited media personnel and spectators—stood in a line behind five metal crates set down in the tawny prairie grass and patches of early winter snow.

Each crate contained one of the first wolves to be reintroduced to Colorado. One by one, each crate was opened, and one by one, each wolf burst forth, away from the confinement of their cages and out into the freedom of the vast, wild expanse before them.

This was the first time gray wolves would roam in Colorado in nearly a century; the last wolf that called the state home was killed by hunters in 1943. The five wolves released on Dec. 18 were the first of 10 to be released in 2023. They were also the first wolves to be reintroduced as part of the Final Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan, which calls for the release of 10 to 15 wolves per year over the next three to five years, in order to create a self-sustaining population of the animals in the state.

But despite the momentous occasion, the fact remained that wolves are not welcome by everyone in the state.

Back in 2020, a ballot measure called Proposition 114 put it up to Colorado’s voters to decide whether or not CPW should reintroduce wolves to Colorado’s Western Slope, the lands located west of the Continental Divide.

The proposition turned out to be one of the closest decisions on the ballot that year—only passing by a razor-thin 50.91% majority. News Press found that the slim majority came from only 13 out of Colorado’s 64 counties, which are home to the state’s major population hubs; the cities along the Front Range and a few counties sprinkled throughout the Western Slope, including La Plata and Summit counties.

Wolf 2302-OR, one of the first five wolves reintroduced to Colorado, runs from its crate on Dec.18, 2023. Courtesy of CPW.

The urban hubs of Denver, Boulder, Fort Collins and their surrounding suburbs alone make up 85% of Colorado’s population—some 5 million people, according to Uncover Colorado. However, those cities dotting the Front Range are on the east side of the Divide, which is a fact that has angered many Coloradans who live in rural communities throughout the western half of the state.

CPW’s Summer 2021 Public Engagement Report found that cattle ranching and business brought in by hunting are major economic drivers for communities throughout the Western Slope, which is why commenters raised concerns about how wolves could negatively impact these two industries by ravaging cattle and elk herds.

Additionally, a survey from Colorado State University’s Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence found that rural voters feel that people on the Front Range—who largely don’t rely on hunting elk or raising cattle to put food on the table—made the decision to reintroduce wolves, without having to deal with the consequences.

But to Paul DeBell, associate professor of political science and assistant dean of impact and innovation at Fort Lewis College, the reintroduction of wolves in Colorado is about more than just the wolves themselves.

Reintroduction is interesting because it speaks to the broader political dynamics of the United States, he said. And one of the themes present in the pro-wolf versus anti-wolf debate are the political and ideological divides between America’s rural and urban communities.

“For the people who supported Prop. 114 and the idea of wolf introduction, it comes to values about environmentalism, and I would say, purity,” DeBell said. “ On the other side, you've got this ethic of hard work and actually living on the land, the rancher perspective, and the fear that wolf reintroduction will threaten that way of living.”

DeBell said whether someone is rural or urban plays into how they vote on a number of other hot-button political issues in the American West—like gun rights, abortion, taxes, immigration or the best use of Colorado River water. Wolf reintroduction is an interesting issue because it plays into many different facets of a person’s life and politics.

“The wolf situation isn't just the wolf situation, and it isn't just the political situation,” DeBell said. “If you think about how somebody who has dedicated their lives to fighting the climate crisis, they're thinking in terms of this epic struggle for survival. It's not just about wolves since it goes into that broader narrative of ecological restoration. On the other side, you think about what it might be like to be a rural farmer and the landscape of small farms being bought up and failing due to water shortages, and thinking ‘I could be the last generation on this farm.’ Wolves are hitting all these sorts of issues on both sides.”

Matt Barnes studying cattle/wolf relations in western Montana. Photo courtesy of Matt Barnes.

Wolves aren’t just polarizing voters in Colorado; states throughout the American West have been caught up in the reintroduction debate. In CPW’s search for a source population of wolves for the reintroduction, it made formal requests to a number of western state governments, including Idaho, Montana, Washington, Oregon and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, according to Travis Duncan, CPW’s Public Information Officer.

Wyoming was not included in CPW’s request. In May, 2023, Gov. Mark Gordon told Cowboy State Daily that his state would not give wolves to Colorado because neither he nor other members of his government approved of Prop. 114.

“CPW made formal requests for wolves with the states outlined in the Final Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan, including Washington, Oregon, Montana and Idaho,” Duncan said. “Conversations with these states are ongoing as CPW’s plan calls for the release of 10 to 15 wolves per year over the next three to five years.”

According to new releases from CPW, the 10 wolves released in Grand County in December were from Oregon, and in January, the organization secured an agreement with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation to source 15 wolves. Conversations with Montana and Idaho continue, Duncan said.

Matt Barnes is a rangeland scientist, wildlife conservationist and a research associate for the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative. Barnes has spent a lot of time in the West’s rural communities, working to find ways to reduce conflicts between livestock, such as cattle, and large predators, like wolves. Like DeBell, Barnes said that reintroduction is an issue that reflects broader themes in today’s political landscape.

“Wolf reintroduction is a biological, philosophical and political issue,” Barnes said. “It's political, because it's philosophical. If you look at the map, it generally reflects the same rural-urban divide that we see in all kinds of politics these days.”

Barnes said that the reason why putting wolf reintroduction up for a vote has become such a touchy issue is because of two misunderstandings: how the state’s legal framework works, and the history of wolves in Colorado.

“In Colorado, we actually have competing state laws,” Barnes said. “We have a state Endangered Species Act which is fairly similar to the Federal Endangered Species Act. That covers wolves, so they are protected under both state and federal law. But we also have a state statute that prevents CPW from reintroducing an endangered species unless authorized by legislation.”

CPW officials examine wolf 2307 before his release on Dec.18

Barnes said that convincing Colorado’s lawmakers to sponsor a bill for wolf reintroduction wouldn’t fly—it would be too risky for politicians seeking reelection. So, because none of the state’s legislators would touch the issue, wolf reintroduction was forced to the ballot, he said.

Another misconception people have is that wolves were migrating back into Colorado on their own, and therefore the need for people to reintroduce them is unnecessary, Barnes said. But, according to Barnes, that isn’t particularly true.

“Colorado had an existing wolf migration plan in 2004,” Barnes said. “When that was written, they didn't think we would need to reintroduce wolves because the first wolf had just shown up from Wyoming. Wolves were federally protected throughout Wyoming at the time. So, there was a reasonable expectation that wolves would find their way to Colorado over time and we would have a wolf population eventually.”

That ended up not being the case. Wolves were delisted from both Wyoming’s endangered species list in 2017 and the federal endangered species list in 2021, according to the Wyoming Department of Fish and Game. Because of their delisting and the implementation of the “predator management zone” in southern Wyoming—where wolves are essentially shot on site as soon as they wander outside the borders of Yellowstone National Park where they are protected—only about 10 wolves have ever been known to make it across Wyoming to Colorado, according to the same CPW public engagement report.

That’s the reason why enough wolves haven’t been able to reestablish themselves without some kind of outside help, Barnes said.

“So that's fundamentally why this is a contentious issue,” Barnes said. “It's because most people don't really understand the legal background. They don't see why it had to go to the ballot.”

Barnes said that wolf reintroduction is so divided among rural and urban voters because many rural voters felt the passing of Prop. 114 was “ballot box biology,” a term often thrown around on social media posts that refers to putting important biological decisions up for a popular, and potentially misinformed, vote. Barnes said the term is dismissive of decades of credited research, and distracts from the real point of Prop. 114.

“Ballot box biology is basically a phrase that’s used to make people want to vote ‘no’ on the issue, or to feel like it should never have even been an issue,” Barnes said. “The reality is, we know the biology fairly well. We know a lot about the biology of wolves. We know more now than we did 30 years ago, because we've been able to study them so well in the Northern Rockies, especially in and around Yellowstone National Park. So there really wasn't biology on the ballot in Prop. 114 back in 2020. The question on the ballot was, ‘should we do this.’”

Prop. 114 actually had very little to do with biology. Instead, it was an introspection into how Coloradans value wilderness, Barnes said.

Nonetheless, the concerns surrounding the wolves from Oregon that were reintroduced to Colorado preying on the state’s cattle were valid. Duncan said that many people expressed these worries to CPW.

“CPW has received many questions on its selection process and whether the wolves came from packs that had been involved in depredation incidents,” Duncan said. “CPW strictly followed the Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan in the selection of the gray wolves reintroduced from multiple packs in Oregon. This plan was informed by Technical Working Group experts and the Stakeholder Advisory Group, and unanimously adopted by the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission.”

Duncan stated that wherever wolves have been, there have been incidents of livestock depredation. However, he said, the wolves CPW introduced from Oregon had an infrequent history of preying on livestock—a fact that would therefore not rule them out from being used in the reintroduction.

“It’s important to note that any wolves that have been near livestock will have some history of depredation, and this includes all packs in Oregon,” Duncan said. “This does not mean they have a history of chronic depredation. If a pack has had infrequent depredation events, they should not be excluded as a source population per the plan.”

But the issue people have with wolves is much older than the 2020 referendum, according to Dr. Andrew Gulliford, professor of history and environmental studies at FLC. Gulliford has been studying the history of the American West for decades, and has taught at FLC for 24 years. His courses dive deep into studying wilderness, national parks and environmental history. Wolves, he said, are the common denominator in all those topics.

“I’m a hunter who welcomes wolves back to Colorado,” Gulliford said. Courtesy photo from Gulliford posing with an eight-point mule deer buck.

“In European culture, the perception of wolves goes back possibly 1000 years, certainly 500 years, as an arch enemy to be found in the forest,” Gulliford said. “So the fear of wolves begins long before America, among Europeans traveling on foot through the forest, where we get all these fairy tale stories about wolves. But those are folk stories. And that's one of the problems that we have to deal with here in Colorado: separating the folk history of wolves from the actual biological history.”

Gulliford said that this deep-rooted animosity towards wolves came with European settlers who wanted to tame the Wild West and make it an easier place to raise livestock, like herds of cattle and sheep. In other words, American settlers didn’t want to compete with another species to be at the top of the food chain, he said.

The fact that Coloradans voted to bring wolves back points to how peoples’ perceptions of wolves are changing. However, the dichotomy in how Colorado’s rural and urban communities value wilderness still exists. And according to DeBell, those opposing views come from the same place: a shared love for the beautiful place Coloradans call home.

“When you look at some of the most polarizing issues, from guns to abortion to immigration to taxes, you actually find there are a lot of people in the middle, but we don't hear about that,” DeBell said. “I think that not just with wolves, but with a lot of issues about the places where we are, there is a lot of shared love and shared concern for where we live and how it's changing.”

DeBell said that the tricky thing with living in the polarized political landscape of 2024 is that the loudest voices, which are often the most hard-line in their viewpoints, are amplified on social media apps and news sources. That can make any political issue feel more divided than it actually is, while simultaneously discouraging constructive conversation and increasing a sense of loneliness.

“What we often see in politics is that the actual issue itself is super complicated,” DeBell said. “And solving it is going to require a lot of really careful consideration and nuance. Yeah, maybe some trial and error. But, again, we get attracted to the sort of nice, clean sense of ‘my side’s right, your side’s wrong.’ And that, I think, is where we lose some really important opportunities to do some good.”

Another term that comes up a lot in wolf reintroduction talks is “coexistence.” Most of the time coexistence is applied to learning how people, livestock and large predators like wolves can live together in one landscape—what Barnes has been studying for years.

But DeBell said that the political issue of wolf reintroduction has the potential to be a way for people from all walks of life to learn how to better coexist with each other. After all, people have always lived alongside wild animals; so the argument among supporters of Prop. 114 that restoring wolves to Colorado will, in a sense, return it to a “pure” wilderness doesn’t acknowledge that Indigenous people have lived here forever, he said.

At the same time, opponents of Prop. 114 don’t always acknowledge that it’s possible for people and wolves to live together. At a certain point, people have to realize that everyone loves this land equally, and that we need to come together to make it a better place, he said.

“I think there's a movement for place-based justice,” Barnes said. “There's a powerful opportunity there. It’s hard, because there's the opportunity, but there's also that conflict landscape, and we're pulled by both. So, which way are we going to go?”

To Barnes, the best way to start down that path of coexistence starts by trying to lay down our opposing opinions and come together to find viable solutions for problems at hand. Now that wolves are back, real conflicts will inevitably arise between people and these animals—like when a wolf kills a rancher’s cow. But in trying to solve those problems, it doesn’t help to point fingers.

“Conflicts do happen,” Barnes said. “But I would like people to recognize when we're being perhaps a little irrational. Or that we're using wolves as a symbol of either wilderness on one hand, or people you don't like on the other hand. Just realize they're neither devils nor angels, they're just animals, and they do what animals do. And sometimes it isn't good for us, but on the whole, it's just part of nature.”

Since CPW works to manage Colorado’s public lands and all of the creatures that live there—people, cows, elk and wolves alike—the organization is committed to helping people understand how to live with wolves, Duncan said.

“CPW is balancing keeping the public informed about gray wolf reintroduction efforts and general gray wolf locations while also working to keep animals and staff safe,” Duncan said. “CPW continues to work with livestock producers to provide conflict-mitigation techniques, and will continue to conduct outreach and education in areas that are likely to have wolves.”

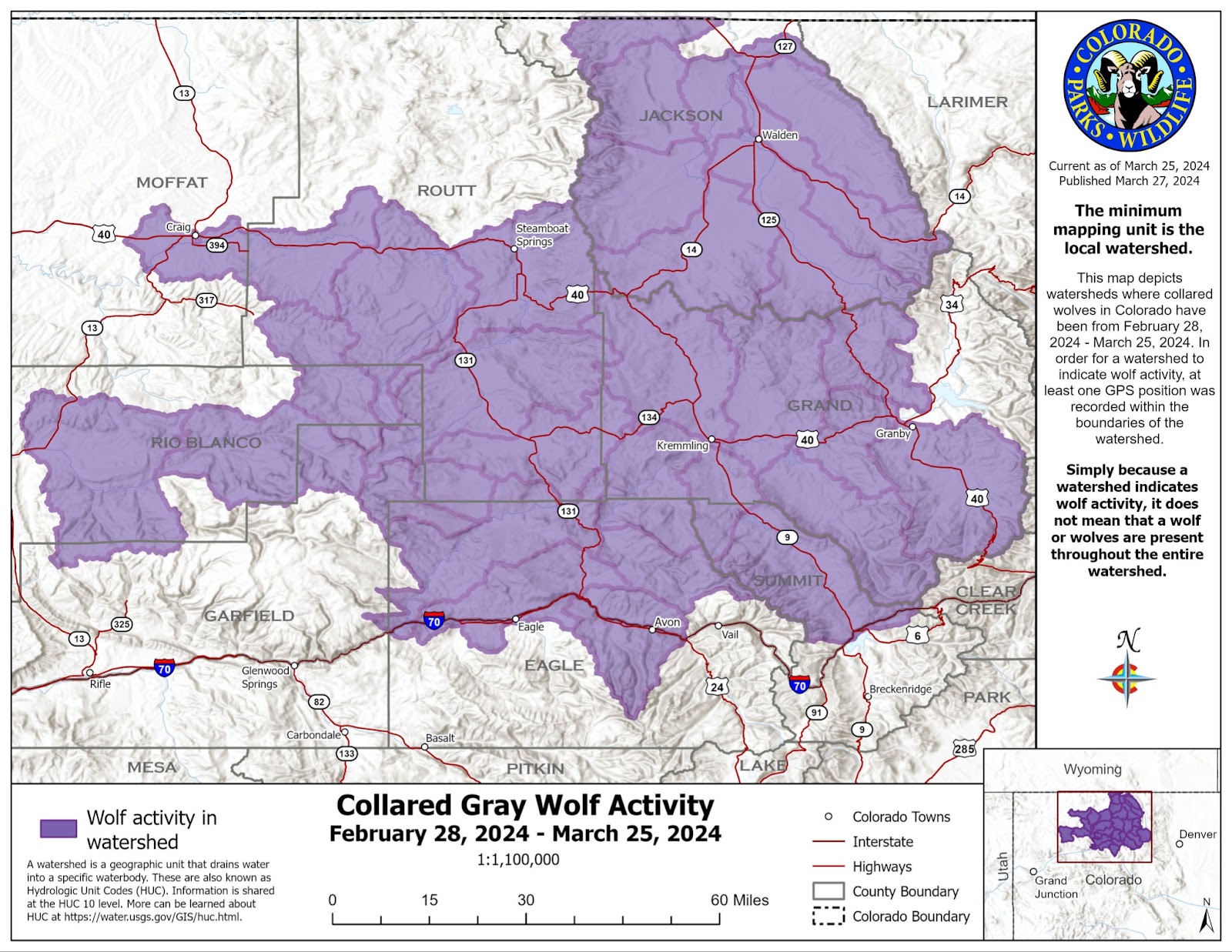

On top of working with the state’s rural ranching communities, CPW created an online wolf map, where the public can learn the approximate locations of Colorado’s wolves. This map will be updated with new information on the fourth Wednesday of every month, Duncan said.

Additionally, Duncan said, CPW continues to encourage anyone who has seen a wolf or wolf tracks to submit a wolf sighting report on their website. The organization receives hundreds of reports yearly, and while they can’t confirm whether every informal sighting was a wolf or not, CPW carefully reviews all credible reports submitted through their Wolf Sighting Form.

But no matter what lies ahead as the effects of the wolf reintroduction unfold, to Gulliford, bringing wolves back has been an example of a functioning democracy.

“I happen to like ballot box biology,” Gulliford said. “Three times, the Colorado Wildlife Commission refused to reintroduce wolves. Then, the Colorado State Legislature decided that we're in charge of endangered species for the state. It was a game of tiddlywinks, jumping over the Wildlife Commission, jumping over the Legislature, and then using the Colorado constitutional code to go directly to the people. That’s extraordinary. It’s never happened in any state.”

Collared gray wolf activity record by Colorado Parks and Wildlife from Feb. 28 to March 25.